|

|

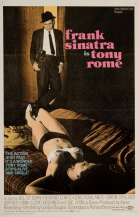

Beyond being a bit of an ego booster for a Frank Sinatra who was, by then, in his 50s, the films’ casual sexism as well as the more than casual homophobia seem to be part of an attempt by an older generation to adapt to the cultural changes brought by the 1960s. Tony Rome especially has a lot of dialogue that was probably deemed risqué for that time, but comes across as mightily forced (for instance, a female character freely admits that she’s used to and okay with being called a slut, there’s an extended bit with an old lady wanting Rome to pay attention to her pussycat, and a small subplot concerns the insatiability of a newlywed woman). Both films feature gay males, but portray them as villainous and pathetic, and while Rome mostly leaves a lesbian couple alone, their relationship is depicted as strange and unnatural, which he can’t resist cracking a few jokes about. The dialogue in general is often rather clunky, drawing unfavourable comparisons to the aforementioned Harper films.

Aside from the period-specific attitudes towards minorities (other than blacks, who don’t make an appearance one way or the other), Tony Rome is an okay character to root for. He’s a serial gambler, but his mild addiction and bad luck make him more lovable than pitiful. He seems to have a code of honour. And unlike his encounters with women, Sinatra’s age does come into play regarding physical altercations, which Rome almost always loses, at least with humans (he shamelessly fends off a whole school of sharks in Lady in Cement‘s opening scene). He gets his arse kicked and threatened at gunpoint numerous times over the course of the two films, without really being able to overpower his opponents (though sometimes, his wit saves him). Sinatra is also undeniably charming in the role, regardless of how eye-roll-worthy the quips he has to say are.

Plot-wise, there’s nothing to write home about in either of the films. The main storylines are largely forgettable, dealing at first with a stolen brooch and a corpse in the ocean, respectively, before getting more complicated without really becoming significantly more interesting.

The background music in Tony Rome (by composer Billy May) is taking turns at being silly and overbearing; Hugo Montenegro’s score for Lady in Cement is better and more consistent, but its swinginess comes at the cost of tension: the music is fine with telling us that Tony Rome is never really in any danger. The villains seem to operate under a similar assumption, leaving Rome alive for no particular reason several times.

What makes the films generally enjoyable after all are mainly Sinatra’s performance (the other acting is much more mixed, especially in the first movie) and the presence of some old-fashioned, traditional gumshoe elements: Rome follows people, pressures fences and corrupt former colleagues, and uses his contacts at an insurance company. He breaks into houses and threatens witnesses (it’s good not to be a cop), impersonates a police detective and manipulates his friend, the police chief (it’s good to have once been a cop). These standard situations are less common in Lady in Cement, which is somewhat balanced by the better music, an overall higher caliber of acting and the fact that the sequel at least plays lip service to the idea that Rome can’t break the law and kill several people and still remain largely unbothered by the police. The movies are also an interesting look at a time before Roe v Wade, when abortions were still illegal (something that is relevant for Tony Rome‘s plot).