I’ve gone on record with my deep aversion to horror films involving gory mutilation of the human body. Consequently, of all the established movie monsters, zombies are the ones I most try to avoid, media-wise. I have neither read nor seen nor played any iteration of The Walking Dead despite good reviews and the involvement of creators I trust. I haven’t watched any of the classic Romero films no matter how many people tell me of their political subversiveness. So it was with some trepidation that I approached Shaun of the Dead, the 2004 cult comedy that put director Edgar Wright and star Simon Pegg on the (international) map.

Thankfully, the gross-out factor stays fairly low throughout the film. The “zombification” that occurs while Pegg’s character is recovering from a break-up via alcoholic binge is mostly played for laughs, which takes the edge off. It is a comedy, after all. That very fact also works against the film, however, whenever it tries to shift the tone to something more serious and heartfelt. The emotions on display don’t always feel earned, and the same is true for the occasional attempts at tension.

Shaun is mildly funny, but I much prefer the same team’s Hot Fuzz (2007), which to my mind does a much better job of juggling affectionate parody with tonal cohesiveness. Of course, maybe I’d feel differently if I’d recognized all the references Shaun doubtlessly contains.

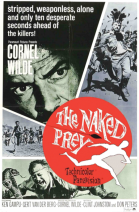

Like the zombie film, The Naked Prey (1966) features a number of unpleasant deaths, this time played horrifyingly straight. After the sponsor of a safari offends a local African tribe, the entire party is captured, tortured and murdered. The only exception is the unnamed character of producer, director and star Cornel Wilde, who is stripped of his clothing and allowed a headstart. He is to provide the local youth with an opportunity to hunt a man for sport. To the surprise of the tribesmen, he really proves himself to be “the most dangerous game“, killing the first of the men sent after him. The entire rest of the film is a chase sequence across the veld that contains almost no dialogue.

The movie doesn’t focus on the white “prey” alone, but periodically shows us his pursuers. Unlike him, they work in a group, and evince a surprising camaraderie. Yes, they’re hunting another human being, but it’s a white man who killed one of their own. They don’t speak English, but they do speak, and it’s clear from their body language that the hunt is affecting them deeply. They’re human, too, complicated creatures instead of cardboard villains. Once the chase was started, their environment forces them into continuing as much as it’s forcing Wilde, and said environment is no particular friend of humans no matter their skin colour. The point is underscored by frequent intercutting of Darwinian wildlife scenery: one animal attacking and eating another, that’s life in the bush. Prey is incredibly thrilling and hauntingly beautiful in its imagery and its stripped-down perspective on human struggle.

This posts’s final subject provides a change of pace and does not feature any death or heartbreak. The 5,000 Fingers of Dr T (1953), a children’s musical with a screenplay by Dr Seuss, is proudly bonkers and nonsensical: A single mother’s son who is fed up with his strict piano teacher falls asleep and reimagines him as a cruel dictator bent on music-assisted world domination which only the boy can prevent by ruining a concert. Also in the dream: the boy’s mother, the local plumber, and a host of all-male henchmen and lackeys.

The plot, which zigs and zags wherever the boy’s subconscious fancy takes him, is somewhat interesting in a Freudian sort of way: to defeat the not so ambiguously gay dictator (portrayed by way of high camp by Hans Conried), who has hypnotised his mother into doing his bidding, the boy must enlist the help of the plumber whom he much prefers as a replacement for his father. The song and dance sequences are decent musically, but more memorable for their getting-crap-past-the-radar subtext: for instance, after a dance between teacher and plumber which is ostensibly about hypnotisation but comes across as more of a courtship tango, the plumber enthusiastically accepts a cigar before singing along with dictator and mother about the “get-together weather” which is just right for “love and assorted courting” and “b-b-b-b-bouncing”.

All of this makes the film a telling historical document about 50’s America’s anxieties about manhood in a time when many fathers hadn’t returned from the war, with some digs towards homosexuality and authoritarian political regimes. It’s not particularly cohesive, though, and it’s not hard to see why critics panned it upon release and Dr Seuss essentially disowned the project. It doesn’t really deserve that — it’s reasonably entertaining. But no more than that.

I suppose all three movies do have something else in common, after all: They’re all a little subversive, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr T in the ways described above, Shaun of the Dead by ever so slightly commenting on the drudgery of modern life and “slackertude”. And The Naked Prey, produced in apartheid South Africa, employed large numbers of blacks and tells a story showing them in an unexpectedly sympathetic light, given the premise.